Why Bengaluru’s draft transit policy is unlikely to make the city more liveable

Dr. Anjali Karol Mohan • Aug 08, 2019

TRANSIT ORIENTED DEVELOPMENT

This February, the Bangalore Metro Rail Corporation Limited (BMRCL) published the Draft Bengaluru Transit Oriented Development (TOD) Policy. On inviting public suggestions and objections on the draft policy, BMRCL got just 32 responses.

To put this number in perspective, Bengaluru’s total population is approximately 120 lakh, of which the working population is around 55 lakh (46 percent). Adding to this, the 5-19 age group which also needs to commute, would peg commuter numbers in the city at an estimated 77 lakhs (about 64 percent of the total population). But, only 28 lakh use public transportation.

Obviously, the commuter numbers are bound to increase. The city’s master plan, the Draft RMP 2031, has projected Bengaluru’s population at 135 lakh in 2021, and at 203 lakh in 2031. Correspondingly, the commuter numbers in the 16-60 age group are likely to increase to 95 lakh (70 percent of the population) and 149 lakh (73 percent) respectively.

Just 32 individuals/agencies giving feedback on a policy instrument that would impact these vast numbers is both dismal and depressing.The poor feedback is attributed to the draft policy not reaching many citizens.

BMRCL had uploaded the policy online on May 8th, with a 30-day window for citizens to submit their feedback. Clearly, both the time given as well as the method of sharing and publicising the draft policy were inadequate. Wider publicity and a longer time frame could have elicited a better response.

My intention here is not to get into the rubrics of an adequate public consultation process, though that is a critical challenge.

The objective of this article is to suggest ways to align the philosophy and the main provisions of the TOD policy with the city’s Master Plan – RMP 2031, so as to proactively steer Bengaluru’s development. That both are in the draft stage is an opportunity the Karnataka government must leverage on priority.

The TOD policy should also be aligned with the Revised Structure Plan 2031 for the Bangalore Metropolitan Region (BMR-RSP 2031), approved recently. The latter part of this article explains why.

What is TOD and why is it important?

TOD is a planning and land development tool that seeks to integrate transit with land use provisions, so as to reduce travel time. TOD envisages dense, mixed land use development along transit corridors. The development should provision employment centres, housing, commerce and supporting services within a walkable distance from the transit corridor and its stations (such as a Metro station, for example).

The main objective is to create walkable neighbourhoods, with easy access to good public transport, so that more commuters can use public transport to reach their destinations in less time.

TOD, it is argued, will create a compact and connected city; and hence generate social and economic benefits like improved health, clean environment, strengthening of local economies and arresting sprawl. In India, where affordable housing is a big challenge, TOD plans prioritise several affordable housing options – including rental and temporary shelter – within the transit zone. Thus, TOD is aimed at helping manage rapid urbanisation processes.

What is Bengaluru’s draft TOD policy about?

The draft TOD policy has set an ambitious agenda for itself. It aims to address challenges like rapid growth of private vehicles, inadequate road network, long commuting time, traffic congestion, road fatalities, and vehicular pollution.

Acknowledging that the state government “has ambitious plans of expanding Metro and suburban rail services in the city,” the policy argues that TOD “will help mass transit to achieve its full potential and aid in sustainable mobility.” To meet its objectives, the policy adopts the 6Ds – density, diversity, design, destination accessibility, distance to transit, and demand management.

Draft TOD policy isolated from several national and state policies

The draft TOD policy comes at an opportune moment given that the central government is now finalising the National Urbanisation Policy Framework. In addition, the centre’s National Urban Transport Policy (NUTP 2014), National TOD policy (2017), Metro Rail Policy (2017) and National Value Capture Policy Framework constitute important reference points for the draft TOD policy. At the state/city level, the TOD policy should talk to the parking and street vending policies.

The intent of all these policies are closely linked to that of the draft TOD policy. Hence the TOD policy has to refer to the larger principles of these policies, to reverse the trend of siloed policies, and thereby, siloed implementation. But the draft TOD policy is weak in straddling these policies, except for the NUTP 2014.

Draft policy limited to Bengaluru Urban, confused about jurisdictions

For TOD to be effective, the policy should align with the land use plans for the city and the region i.e., the RMP-2031 and the BMR-RSP 2031 respectively. The statutory premise for such an alignment is in the NUTP 2014 as well. NUTP emphasises a mobility plan that integrates both land use and transport planning, through TOD.

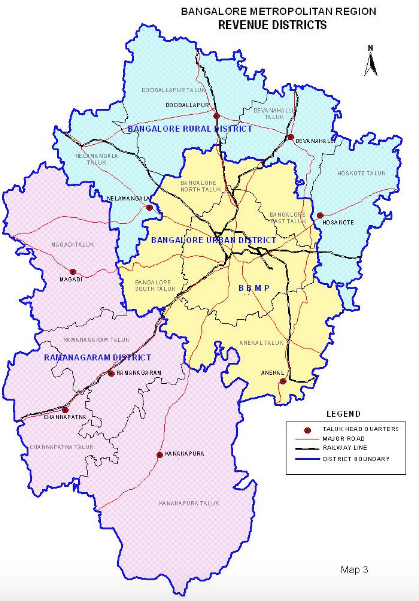

The draft TOD policy does acknowledge the provisions of RMP 2031. But it has a muddled understanding of the planning and administrative jurisdictions of Bengaluru. What it refers to as the Bangalore Metropolitan Region (BMR), is in effect, the Bangalore Metropolitan Area (BMA – 1250-odd sq kms).

The BMR is 8000 sq kms, and comprises three districts – Bangalore Rural, Bangalore Urban and the Ramanagara-Channapatna district. It comes under the planning jurisdiction of the Bangalore Metropolitan Regional Development Authority (BMRDA). In contrast, the BMA is spread across just 1250-odd kms, and comprises of the Bangalore Urban District alone.

Similarly, what the policy mistakenly refers to as the BMA is in effect, the 712 sq km municipal area administered by the BBMP and planned by the BDA. It is the core of the Bangalore Metropolitan Area, not its entirety.

In any case, the draft policy restricting itself to the BMA of 1250-odd sq kms is short-sighted. Transit has a regional character both in its use and the required infrastructure. Hence, limiting it to the city would be a fragmented approach.

More critically, the policy will then fail to service the outlying and transition areas, which require transit interventions on priority. These areas are also spatially, and from an economic lens, fertile grounds to implement TOD.

Bengaluru needs a ‘mobility plan’, not a mere ‘TOD chapter’ in the Master Plan

The draft policy notes that the RMP 2031 advocates TOD, but that it does not propose land-use strategies accordingly. The policy goes on to say that “TOD Policies shall be incorporated in the Master Plan”, suggesting a revision of the RMP’s Development Control Regulations in line with the philosophy of TOD. Further, the Master Plan should have a separate chapter on TOD, describing the overall objective, demarcation of TOD zones, land-use and transport strategy, says the draft policy.

But Master Plans are the overarching and the only statutory tool, that can incorporate a multi-sectoral analysis – including transport – to guide and steer the city’s growth, coordinate service delivery, provide infrastructure and other day-to-day requirements of citizens. Thus, they have a larger, comprehensive vision of the city as against sectoral plans and policies.

Hence, instead of the mere “insertion” of a TOD chapter in the Master Plan, the draft TOD policy should mandate the preparation of a mobility plan itself. This mobility plan should incorporate the mandates of TOD based on the provisions of the Master Plan. And it should be notified as a statutory tool, either independently or appended to the Master Plan. It should simultaneously draw from and guide the RMP. As of now, the mobility plan is neither mentioned in the draft policy nor is it a part of the RMP 2031.

TOD strategies don’t consider the varied growth patterns within city

Since the different planning zones (A, B and C) in Bengaluru have varying development patterns, the Master Plan proposes different planning strategies for each of these. The draft TOD policy does acknowledge this differential growth strategy of the Master Plan, but does not draw upon it while framing TOD strategies.

The draft policy merely states that TOD will be implemented based on land availability. But contextualising the varying development trajectories within BMA will help design nuanced TOD packages.

For instance, implementing TOD projects in the core city (the erstwhile BMP of 200-odd sq kms) – that is, planning zone A – is a challenge. This is because of the high densities and high property values within this zone. But, as we move out radially from the core towards the periphery, implementing TOD is relatively easier. It is perhaps more relevant too, as a proactive measure to control city sprawl.

Policy focuses on Metro and suburban rail, not buses

Also, the draft policy focuses largely on the Metro and suburban rail, and only makes a fleeting reference to buses and bus transit corridors. The lack of adequate focus on buses as a public transit mode is a gap that needs correction.

In sum, the draft policy should:

- adopt the jurisdiction of the entire BMR

- emphasize the need for a mobility plan for BMR

- arrive at a land-use strategy that links with all modes of public transport.

Another point is that the policy is premised on the ‘premium FSI’ concept. FSI (Floor Space Index) is the ratio of a building’s gross floor area to the size of the plot on which it’s built. A higher FSI allows the developer to build high-rise structures. To achieve dense, mixed land-use development, the TOD policy allows a premium FSI that’s above the base FSI.

But builders hardly follow FSI regulations in Bengaluru anyway, in the hopes that building violations would later be regularised as per the state government’s long-pending Akrama Sakrama scheme. Given this, the likelihood of a successful ‘premium FSI’ is bleak.

The policy also takes a stand that “Steep penalty shall be imposed for violations. In case where building violations have severe negative impact on the surroundings, buildings shall be demolished. Adequate staff shall be deployed for monitoring the building violations.” But it is not clear who will be doing this – the BMRCL, or the municipal corporation whose core function it is anyway.

Clarity on these aspects is a must to evolve a meaningful mobility plan and an attendant land-use strategy.

The draft also suggests GIS mapping to identify and manage violations. Such a detailed exercise was already done as part of the RMP 2031. The same should be used or built upon further, instead of starting from scratch.

Lastly, it is laudable that the draft TOD policy earmarks a budget for communication and outreach. The government should use this in moving the policy from the draft to the final stage. Eliciting inputs from citizens and other state and non-state stakeholders to frame a more comprehensive, coordinated policy that informs and is informed by the Master Plan, is the need of the hour.

By Networking Session by INDÈ at the Global Gobeshona Conference-2

•

01 Apr, 2022

Being a member of the Adaptation Research Alliance, ARA (a global, collaborative effort to increase investment and opportunities for action research to develop/inform effective adaptation solutions) and an ARA Micro grantee, Integrated Design (INDÈ) was invited to organise a networking session at the Global Gobeshona Conference-2 (conference theme: exploring locally led adaptation and resilience for COP27). The networking session was titled ‘Situating Urban (City) Resilience within the City-Region’ and was held on 1 April 2022.

By Dr. Anjali Karol Mohan

•

04 May, 2020

The online magazine SustainabilityNext carried an article by Benedict Paramanand titled “Has Fatigue Set into Civic Activism in Bengaluru?” The article caught my eye amidst the Covid 19 humdrum as I was looking for alternative news. I have been actively engaged in the debates around the (ill)growth and mis(management) of Bangalore for over two and half decades in my capacity as a professional planner straddling civic society, public policy circles and academia. The article revived in my mind some thoughts and suggestions that I articulate here. The attempt is not so much to answer the question, as it is to understand the shortcomings and limitations of civic activism in steering the complex politico-socio-economic and cultural layers that make up a vast conglomeration like Bengaluru. A disclaimer here merits mention. The premise that no individual stakeholder, public or private, has the knowledge and resources to tackle the wicked problems underpins successful governance arrangements. What this premise implies, by extension is that all stakeholders – public or private – have limitations. Civic Society (CS) is one amongst the numerous stakeholders that have a role – by no means a lesser one- to play. Yet, there are limitations to this role. While these limitations are embedded in the very nature of operation of the CS, there are conscious ways and means of overriding some limitations to move towards a larger impact. Bridging limitations is a critical need. Much of what I articulate while contextual to Bengaluru, perhaps holds true for civic activism across domains and geographies. To begin with, a critical question requiring reflection is the difference between civic activism and the much advocated (in (good) governance debates) Civic Society Organisation (CSO) engagement. These generally get clubbed in one category – while in theory and practice, that is not the case and therein lies the first limitation. Activism defined as direct vigorous action especially in support of or, in opposition to, one side of a controversial issue is willy-nilly an act of reaction. Reaction often leaves little space for taking distance and exploring the systemic cause of the challenge – the challenge itself sets the agenda. In contrast a proactive engagement of the civic society, through progressive partnerships while also triggered by a challenge is different in that the challenge is anticipated and therefore the agenda is set by civic society themselves. In Bengaluru, protests against the state-imposed flyover (# steelflyoverbeda ) and elevated corridors (# TenderRadduMadi ) is an example of the former. In contrast, the long-standing work on the ward committees which has seen some traction in the recent past – albeit slow and tardy – is an example of the latter. Having started as a proactive CSO engagement, the movement for neighbourhood planning and governance through ward committees (# NammaSamitiNamagaagi ) in the recent past has bordered on being reactionary, thereby hinging on activism. Although an ‘always proactive approach’ is not possible, given the capacity of our government to spring surprises, it is critical that the CS begins to move towards a proactive stance. There will always be a non-uniform interplay between being reactive and proactive. A second limitation, linked to the first, is the lack of capacity of the CS to act on relevant and practical evidence. This will require the CS to open their doors and develop progressive partnerships, including partnerships with policy makers, professionals (note that I do not use the word experts) and academia. An all-time reactionary mode of operation allows neither for collaborations nor evidence. Evidenced advocacy and conversations require domain knowledge (experienced domain knowledge is even better) which can facilitate knowledge production and mobilization. Activism hinges on passion (amongst other drivers) which is not the same as domain knowledge and knowledge mobilization. Both passion and domain knowledge have a role, yet the two can neither replace each other nor should be confused. Rather, passion that pivots on evidence and knowledge is a double-edged sword, one that has the capability to steer reactionary behavior to an informed proactive engagement. Such a move will serve to, over a period of time, course correct policies that are currently influenced by dominant political structures, electoral volatility and elite capture, as against being evidence based. A third limitation that needs consideration is the nature, purpose, goal and objective of the civic society coalition/group. Most often mobilisation is around a seemingly common purpose, goal and objective. For instance, groups that coalesced against large infrastructure projects as mentioned above or the demand for footpaths and public transit (# BusBhagyaBeku ) and sub-urban rail (# chukuBukuBeku ) are not homogeneous. It is often a mixed bag as against an imagined and perhaps desired integrated unit. Underpinning this pursuit of collective goals and objectives are individual desires, identities (which in themselves are multiple), beliefs, perspectives and previous experience, all of which are critical drivers, often leading to fragmented voices. This fragmentation notably, also derives from the inability to use evidence or domain knowledge. Elitist Activism Furthermore, activism in itself is and can be elitist. When linked to high levels of access it can be potentially hampered by what is referred to as ‘elite capture’. There are two types of activism: elite activism stemming from mobilization of charismatic individuals capable of getting their voice heard. Mass activism, in contrast, is where the general public, the haves and the have-nots, mobilize collectively. The two are not mutually exclusive, although both are critical. Barring a few occasions, Bengaluru’s activism has been elitist with a few voices that can access public policy corridors and therefore get heard. Consequently, consciously or unconsciously there is a leveraging of public policy for personal or limited gains (to a neighbourhood or a community). Activism is a luxury that not everyone can afford. Those who can afford it have a dual responsibility of using it to build bridges by roping in knowledge and experience on one hand and ensuring inclusion by creating spaces and opportunities for mass activism, on the other. The current modus operandi lacks on both counts. These shortcomings have led to what is being referred to as limited success, although limited from whose lens and success for whom is an additional enquiry, one that merits a separate post. What I do concur with is that at best the city has seen some cosmetic changes. Let me take the same two examples the article uses to demonstrate a going forward beyond cosmetic progress. First are the lakes in Bangalore that have seen a fair bit of activism. In many neighborhoods, thanks to the many charismatic residents, lakes have been claimed as better maintained natural resources. But for the initiatives of a few citizens, many lakes would have morphed into real estate projects. Yet, the same groups have done little to engage the larger neighborhoods to ensure that these natural resource ‘spaces’ become public ‘places’ for the neighborhood and the city. This would require a proactive engagement in identifying the larger neighborhood and the numerous linkages – backward and forward – that this neighborhood has had and can nurture with the lakes as public places. The second is the Tender Sure roads pioneered by Bengaluru. The implementation of Tender Sure roads is progressing incrementally moving from a pilot in the city core to radiating outwards in various directions. Putting aside the debates on the efficacy of the design as well as the appropriateness and relevance of the idea, the incremental implementation is marked by controversies on the criteria to shortlist roads such that both the visibility of and utility to the neighborhood and the city can be maximized. This too has not happened. Both these examples offer a critical insight: that the activism (and the few instances of engagement) has not translated into a thinking city. Changes are still hovering around the thinking individual. The transition to a thinking city is an emerging imperative, one that demands systemic change along various dimensions, some of which I have discussed above. To sum-up, sustained and big bang change as against cosmetic and incremental change is the need of the hour. It requires at the outset, one, more proactive engagement and less reactive activism; two, passion combined with experienced domain knowledge to trigger evidenced advocacy and change; and, three a less fragmented approach through creating meaningful spaces for mass activism along with the existing elite activism that the city has. While there may be numerous ways to act on these three, the Ward Committee space offer a ready platform for proactive action, evidence-based advocacy and wider participation. Arguably, this space is rife with political contestations and may seem a daunting challenge, yet, an engagement within this space is a surer foot forward. Clearly, there is a passion amongst Bangalore’s elite to be part of something bigger and this is a moment to be seized.

VISIT

3406/2 (784), 10th Main, 34A Cross, Jayanagar 4th Block, Bangalore 560011, Karnataka, India

CONTACT

+91 80 266 31398connect (at) integrateddesign (dot) orgwww.integrateddesign.org

©

Integrated Design

VISIT

3406/2 (784), 10th Main, 34A Cross, Jayanagar 4th Block, Bangalore 560011, Karnataka, India

CONTACT

+91 80 266 31398connect (at) integrateddesign (dot) orgwww.integrateddesign.org

©

Integrated Design

VISIT

3406/2 (784), 10th Main, 34A Cross, Jayanagar 4th Block, Bangalore 560011, Karnataka, India

CONTACT

+91 80 266 31398connect (at) integrateddesign (dot) orgwww.integrateddesign.org

©

Integrated Design